Reflections on an old-time piano teacher, Gladys Fanton

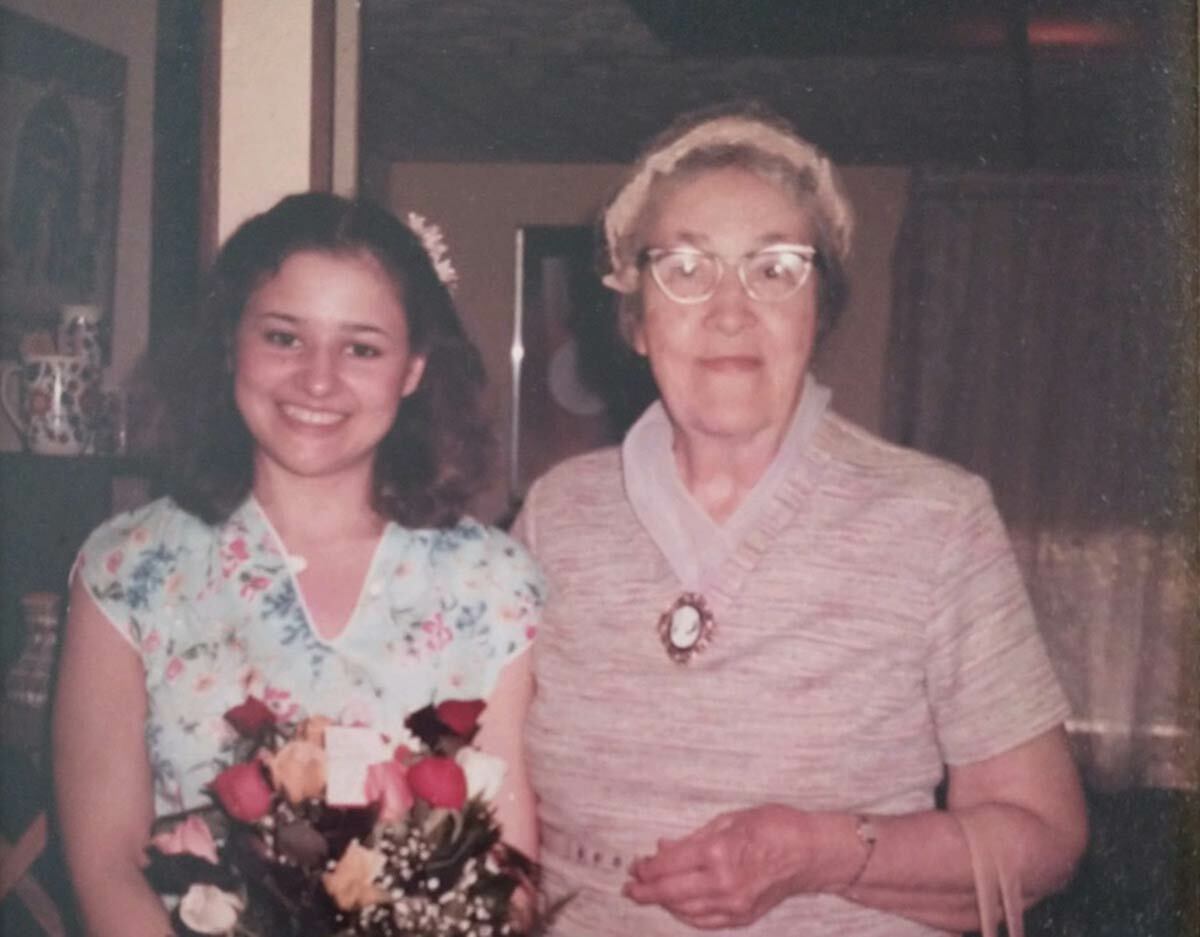

A 21-year-old Isabella Eredita-Johnson with her piano teacher, Gladys Fanton. Photo courtesy of Isabella Eredita-Johnson.

We rely on your support to share good news!

Become a supporting member today.

Born in Brooklyn to immigrant parents, Isabella Eredita-Johnson moved to Northport in 1960. She was one year old. Still a resident, she maintains a lifelong love of her hometown, and likes to reminisce about growing up here. Her brothers had paper routes, and the siblings remember when McDonald’s and Grand Union (now Ace Hardware and Walgreens) were vacant land.

Below she recounts lessons learned from her piano teacher, Gladys Fanton. “Gladys was certainly an ‘old timer,’ and told me many stories about taking the trolley into Northport,” Eredita-Johnson told the Journal. “She was organist of the First Presbyterian Church of Northport for 55 years, though she made it clear she was a Methodist!” Fanton was a member of St. Paul’s Methodist Church on Main Street which, coincidentally, is where the nonprofit Opera Night Long Island (ONLI), founded by Eredita-Johnson, holds monthly performances.

Another coincidence, Eredita-Johnson says, is that kindergarten was held at St. Paul’s in 1964, when she was a student (the public school had no room for the kindergarteners at the time, so they were bussed to St. Paul’s) and currently, ONLI’s opera night room, where a piano, music and some costumes are stored, is in the very classroom in which Eredita-Johnson attended her first year of elementary school.

The following excerpts were taken from an article written by Eredita-Johnson nearly two decades ago. Read the story in its entirety (and find out the fate of Miss Fanton’s grand piano) here.

Often, our initial experiences with something can become the defining ones. I believe this is true of my years with my first piano teacher, Miss Gladys Fanton. I began lessons with Miss Fanton in 1970, when I was 10 years old. She was 68 and semi-retired, living and teaching in a turn-of-the-century Victorian-style home along tree-lined Main Street in Northport, Long Island. My mother accompanied me for the first lesson, leading me through the whitewashed wooden gate, across the pine-planked porch, and to the door of the brown shake house. Miss Fanton met us there and welcomed us in. She appeared quite prim and proper, tall, with angular facial features and steel-gray hair fastened into a bun – like a one-room schoolhouse teacher….

This was a no nonsense woman. I was a little apprehensive, but Miss Fanton was sweet and reassuring. We got straight to the lesson.

As my mother sat quietly across the room she gave me a run-down on reading music, and then we played a basic five-finger exercise with hands together. Soon she was insisting, “Isabella, proper hand position. Curve your fingers, don’t collapse them. Wrists at even height.” I had come to the lesson wanting to play a melody as soon as possible, but Miss Fanton kept me on the basics. She played for me a beautiful short piece of music and I asked her its name. She told me it was simply “an inversion of arpeggios in a harmonic progression.” I didn’t really know what she meant, but at the end of the first lesson I told her, “Miss Fanton, when I grow up I want to become a concert pianist.” She replied encouragingly, “If one truly loved what they were doing and were willing to work hard enough at it, then any possibility may exist.”

Before long our lessons settled into a comfortable routine. I would ring the doorbell, let myself in, and go directly to the piano to brush up on my scales and run through my pieces. After about 20 minutes, she would come downstairs and begin the lesson. For the next hour and a half she would teach theory and technique – instructing, listening, commenting. Miss Fanton was a diligent teacher, always quick to detect and correct any bad habits I might begin to develop, but she was no drill instructor; her style was always kind and patient. She used method books, but they were basic books that used traditional techniques. And unlike many of today’s teachers, myself included, she always gave hour-long lessons. She believed that a lesson needed to be at least that long, and that in a half hour one could not possibly get everything in.

But Miss Fanton’s lessons lasted more than an hour, sometimes over two hours. The extra time was usually taken up with stories from her musical and life experiences. These stories were often what I enjoyed most about our time together. She loved to describe the way Northport was in years gone by – taking the trolley down to the harbor at the end of Main Street on a late afternoon when the baymen were unloading their bushels of clams and lobsters onto the dock, or visiting the dairy farm on Oak Street, which was only a few blocks away. She talked, also, of summers when [Russian-born composer Sergei] Rachmaninoff lived in the town next to ours. He would drive his boat to Northport and visit the home of the harbormaster, Dexter Seymour, often performing for a select group of locals in a salon-like setting. Miss Fanton was a friend of Mr. Seymour, but she never had an opportunity to visit with the great pianist during these occasions. She often lamented that she would have loved to have been invited….

Miss Fanton wasn’t a virtuoso and did not herself perform in public, but she was a capable pianist who had a flair for teaching. Her repertoire included Bach Preludes and Fugues, Beethoven Sonatas, Debussy Preludes, and many of the technical studies of Hanon, Schmitt, Heller, and Czerny. She did impress upon me, however, the importance of performing for others as a part of my training. Often during our lessons friends would come for brief visits, and she would have me perform a piece that she felt I had mastered. I see now how valuable those little one- or two-person audiences were for my confidence.

Miss Fanton also regularly attended a local concert series. She sometimes bought an extra ticket for me, and we would go together. My mother would drop me off at her home. I would wait while she finished her grooming preparations at the mirror by the door. The last step was always the donning of her white pillbox hat. That’s when I knew she was ready. We drove to the concert in her mint 1966 Rambler with a manual transmission, and on the way she would talk about who was to play and what they would be playing. What I remember most of our first trip, however, was the flawless way in which she clutched and shifted gears….

I said earlier that Miss Fanton was not a public performer, but this is not entirely true. She did play the organ each week in public for Sunday services at the Presbyterian church in town. She did this for over 50 years. It was another one of her joys. She was a very religious woman, and she spent much of her time talking about her devout beliefs. I believe that she tried successfully to live up to them. Her father had been a Methodist minister, and she was no rebel. She kept the old time values in many ways, not the least of which was the fact that she never married—in keeping with the old fashioned idea, perhaps, that a woman cannot both marry and have a career. Her life’s loves were her God and her music.

After the passing of her parents, Miss Fanton lived with her brother, Lloyd, until his death in the 1960s. Lloyd was an unusual character and very different from her. Miss Fanton often entertained visitors even into her nineties, and after arthritis had made dull tools of her fingers, her piano would frequently be covered with cards and gifts from friends who had come by. But Lloyd was a bit of an eccentric and not nearly as social as his sister. Often he could be seen walking about Northport in a wide brimmed hat with his pet raccoon on his shoulder. He had taken a degree in business at college and spent most of his life working for an insurance company. His talent was for numbers and details.

Miss Fanton loved to tell the story of how, earlier in their lives, his talent for details had served as an instrument of good fortune for her. A piano company had published a contest in a local newspaper. A picture of an upright piano had been cut into pieces, and each week a segment of the picture was printed in the paper. The contestant’s job was to reassemble the squares, paste them together, and submit the correct picture before the deadline. The prize was the upright shown in the picture. Lloyd took on the job and did it so well that when his father held the picture-puzzle up to a light he could not see even a trace of the seams between the squares. Lloyd won the piano for their home, and it became Miss Fanton’s first. She never did get rid of it, even after she bought the grand piano with which she taught lessons.

[Miss Fanton’s] passing was not tragic—she was 98 years old and had lived what I believe was a joyful and fulfilled life. Still, I can’t help but feel a great sense of loss—of a good friend, of a mentor, of an era that forged my conceptions of great music, great performance, and great teaching.

Most of us remember that one teacher who most inspired us to work hard and to set our goals high. We can remember the one who was the most kind, the most patient, or the ones who most piqued our interest in the world of music with rich stories of their personal experiences. For me, Miss Fanton was the one who did all of these things.

Over the last several months I’ve been thinking about what I believe we’re all losing as the “Miss Fantons” of the world pass on and the old methods of teaching seem to pass on along with them. I’m sometimes tempted to think that, too often, the study of the piano is considered by parents to be just another activity for their child, just another stop between soccer games and the movies. I’m reminded of the parent who bitterly objected to my comment to a student, one day, that if I had to grade her progress from the prior week, it would be a C.

I can’t blame her for feeling that way. It seems that the idea of rating the child’s performance clashed with that parent’s sense of modern education. We had opposite views – she thought it was about self esteem, I thought it was about accomplishment. I, for one, think that if a teacher knows a student hasn’t practiced, she ought to be allowed to call that student to task.

Similarly, we ought to be able to expect and encourage excellent effort. As a piano teacher, I want to rightly say of my profession that we are not just activities coordinators, rather, that we are teaching a skill that is difficult to master, an art that takes real dedication to create. Miss Fanton seemed to live in and foster a world where these possibilities did exist. I hope that when I'm older and semi-retired I will have developed the qualities that made her a great teacher. And I'd like to offer this article as a memorial to my first teacher, to all our first teachers.

Find out more about the opera nights happening right here on Main Street in Northport Village on the ONLI website. The next performance is on February 10. Still reading? Check out this 2011 NY Times article about those Rachmaninoff visits and how then 13-year-old student Ellie Horn teamed up with her piano teacher, Isabella Eredita-Johnson, to raise funds to replace the historical marker sign that once proclaimed Rachmaninoff’s connection to the area.